It’s Sunday night, October 17, 2004. The Yankees have won the first three games of the American League Championship Series and they lead 4-3 in Game 4 at Fenway Park. It’s the bottom of the ninth inning, and the Red Sox are three outs away from a long, cold winter.

It’s Sunday night, October 17, 2004. The Yankees have won the first three games of the American League Championship Series and they lead 4-3 in Game 4 at Fenway Park. It’s the bottom of the ninth inning, and the Red Sox are three outs away from a long, cold winter.

Yankees closer Mariano Rivera would face the bottom three hitters in Boston’s lineup: Kevin Millar, Bill Mueller, and Mark Bellhorn.

JOE TORRE, Yankees manager:

If there’s one thing I can second-guess myself about, it’s Mo going out in the ninth inning. . . . I was going to go to him and tell him, “Don’t get too fancy. Go after him. Don’t worry about trying to make too good of a pitch.” The only reason I didn’t say anything is I remembered the last time he had faced [Millar], in Game 2. . . . Because of how easy that at-bat was, I said, “Fuck it.” Because I didn’t want to plant a seed that wasn’t there. It was so easy the last time.

TERRY FRANCONA, manager:

You try to set up the inning in advance. If this happens, this is what we’re going to do. I was down in the tunnel with Dave Roberts and I said, “Millar is going to get on and you’re going to steal.”

KEVIN MILLAR, first baseman:

There was never a panic because at that point, we had nothing to lose. But if you sit back and look at the big picture, you’re going, “Holy shit.” You’re down three games, you’re down in Game 4, you got Mariano Rivera trotting in with the greatest postseason ERA of any closer—holy shit, right? That’s the big picture. The small picture is, I got to get on base. People ask me, “What were you thinking?” and, honest to God, I was thinking homer. That was it. Fenway Park. I loved hitting there, it’s a short porch, Mariano throws fastballs, I’m a pull hitter, I’m trying to pull a homer.

Rivera had retired Millar in a tight spot in Game 1 and had struck him out swinging to end Game 2. In the stands, everyone was standing. Fans were hoping, praying, pleading for the Red Sox to score. Fans in the front rows pounded on the padding in foul territory, trying to make as much noise as possible.

Rivera’s first pitch to Millar missed inside.

CHRIS CUNDIFF, batboy:

I looked over at the batboy the Yankees brought up from New York and thought, This is so unfair. They enjoy this every year. In 10 minutes, he’s probably going to be so happy and we’re going to be all sad again. But as soon as Rivera threw ball one, I thought, Well, you know what? If he can walk here, you never know.

Rivera’s second pitch was out over the plate, and Millar lined it foul into the third-base grandstand.

KEVIN MILLAR:

I was looking for something middle in I could pull. Mariano made mistakes to right-handed batters. I was pretty confident that if he made one, I could get it. At 1–0, I tried to hone in on a pitch, and I lined it near their dugout.

The clock above the Fenway center-field bleachers clicked from 11:59 PM to 12:00 AM. It was Monday morning. A new day had begun.

Rivera’s infamous cut-fastball usually runs down and away from right handed hitters. But his next three pitches were all inside, each one a little further up and in, well out of the strike zone. Millar found none of them enticing. He backed away from ball four, ducked his head, and trotted to first.

KEVIN MILLAR:

Ball four really wasn’t that close, which sort of surprised me because once it got to three balls I thought they’d come after me a little more. It’s not like I was Manny or Papi and needed to be pitched around. I’m proud that it was a disciplined at-bat, though, because what we needed was a base runner. Though a homer would have been pretty cool, too!

JOE TORRE:

Even though he’s the best doesn’t mean bad things don’t happen. I think he was trying to be too careful with Millar. And that’s what happens in a one-run game in this ballpark. I can’t fault him for it. You certainly don’t want him to throw one down the middle.

Rivera’s pass to Millar was the first unintentional walk he had issued in his last 35⅔ postseason innings, a total of 134 batters dating back to 2001.

THEO EPSTEIN, general manager:

As soon as Millar dropped his bat on the plate, I think everyone knew what would be coming next. We just needed the visuals. And then Roberts came out of the dugout.

DAVE ROBERTS, outfielder:

Terry told me at the top of the ninth that I’d be running for whoever got on. Right before I was going to take the field, he looked at me and gave me a wink. And I knew what that meant.

TERRY FRANCONA:

That was my way of saying, “Go get ’em, big boy.”

KEVIN MILLAR:

I couldn’t get off the bag quick enough, knowing they’re going to pinch-run Roberts—get my slow butt off the bases. No words were necessary. It’s not like I was about to give him base-running advice. So I gave him the knuckles, got off the field, and tried to get some elbow room by the railing to watch him go off to the races. We knew he was going. The Yankees knew he was going. Are they going to pitch out? Are they going to slide step?

DAVE ROBERTS:

I was scared and excited. I can’t tell you how many emotions went through me. To be honest, the fear of being the goat definitely went through my mind because I hadn’t played in 10 days and didn’t feel fresh. I knew in my mind what I wanted to do, and I had to hope my body followed. I remembered being on a back field in Vero Beach in 2002. Maury Wills told me that at some point in my career there will be an opportunity for me to steal a base, a big base, and everyone in the ballpark knows I’m going to steal, and I can’t be afraid to steal that base. Did I think it was going to be in the ALCS against the Yankees while I was playing for the Red Sox? Absolutely not. But when I was jogging out there, I realized, This is what Maury was talking about. This is my opportunity. Don’t be afraid to take this chance.

When Roberts got to the bag, first-base coach Lynn Jones told him Mueller would be bunting.

DAVE ROBERTS:

Third-base coach Dale Sveum initially flashed the bunt sign for Bill, assuming we’d sacrifice. Terry hadn’t sent it. I told Jones, “No, no, no, I’m going to steal.”

Jones had a flash of panic. He quickly got the attention of the Boston dugout, and Roberts made a rolling motion with his left hand across the diamond at Sveum: Go through the signs again! It took a few seconds to get the strategy straightened out. There would be no bunt.

LYNN JONES, first base coach:

I told Dave, “Do what you do.”

Roberts took a huge 3½-step lead, daring Rivera to throw over. If Rivera could get Roberts to shorten his lead by even a few inches, it could mean the difference in a close play at second base.

DAVE ROBERTS:

From running against Rivera in that series in September in New York, I knew what he would do to try to defense me, and that’s the way it played out. They held the ball on me, trying to catch me jumping, so I made sure not to be too eager. If he had gone to the plate right away, I don’t think I would have made it because my legs weren’t under me yet. As a base runner, it’s important to know that the pitcher is not going to quick-pitch you once he gets set. It gives you a couple tenths of a second to calm your nerves and stay relaxed and then be ready to steal. That’s what I was banking on right there. If Mariano had come set and went right to the plate, I wouldn’t have been ready to go because I was waiting for that hold—that 2⁄10 of a second hold—that extra-long hold. And so Mariano picks over one time. And the emotions start to dissipate a little bit. And he picks over a second time. And then the nerves really calmed and I was at peace.

ALAN EMBREE, pitcher:

When he almost got caught, you’re going, “Oh no, oh no, not that way. Come on, stay close now. We know you’re going, but don’t get picked off.”

DAVE ROBERTS:

That second time, I felt like I was a part of the game. And the third time, I felt like I had played the whole nine innings.

LYNN JONES:

There was no doubt the pickoff throws heightened his senses. It allowed his muscles to start reacting. It was perfect. It couldn’t have worked any better. The throwovers were exactly what he needed. They helped take those jitters away. He kept moving out there a little bit further, and we’re talking about inches, but when you’re out there that far, holy smokes. He’s way out there.

DOUG MIRABELLI, catcher:

That guy got the biggest lead I’ve seen from any stealer. And he was still able to get back to first base. He needed every inch of that lead, that’s for sure.

DAVE ROBERTS:

After the third throw, I was ready to go. I was thinking there’s no way somebody throws over four times. Just instinct, I guess. A base-stealing instinct. I was waiting for that move of his going to the plate. As far as a key, whether it be a knee or hip or shoulder, it was nothing like that. As soon as I saw movement, I was gone. If he had thrown over one more time, he would have picked me off.

Rivera did not throw over a fourth time. On his move to the plate, Roberts took off. Rivera’s pitch to Mueller was outside, at the letters. It wasn’t a pitchout, but it functioned like one for catcher Jorge Posada.

BILL MUELLER, third baseman:

I was hoping I would get enough pitches so that Roberts could pick one and steal. That was my main concern once the bunt came off—either moving him over to second or making sure that I allowed him a chance to steal. And making sure that I don’t go after the ball if he takes off. At that moment when your eye catches movement from the base runner, you don’t want to move a muscle. I’m going to let this play out and then we’ll deal with the situation after that.

Posada caught the ball in his left hand while simultaneously coming up out of his crouch and cocking his right arm. His throw was strong but slightly off-line to the left, tailing away from the base and the runner. With a left-handed batter at the plate, Derek Jeter was covering second. He reached forward for the ball, trying to speed up the play, then quickly brought his glove back for a tag. Roberts went in head first. As his left hand hit the base, Jeter’s glove was perhaps six inches away from Roberts’ left arm.

TERRY ADAMS, pitcher:

It was a bang-bang play. He was clearly safe, but it could have gone either way. It was one of those plays where you see guys get called out who were more safe than that. We were also fortunate enough to go into the clubhouse and watch things like people at home would. We saw it in slow motion over and over and over again.

DAVE ROBERTS:

I thought I was in there pretty good, but then you go back and look at footage and you realize how close a play it was. . . . The crowd was buzzing, but once I got out there to run, there was a peace—a calm. Then when I got into that sequence with Mariano, it was dead silent. Lynn told me, “Do what you do.” After that, the next thing I heard was Derek Jeter putting the tag on me and me brushing the dirt off and him saying, “How the heck did you do that?”

CURT SCHILLING, pitcher:

The whole thing was surreal. Everything he’d ever been taught about stealing bases was on display there. The lead. Knowing the pitcher. The jump. The slide. Everything. And he had to do every single one of those things perfectly, or he would have been out. At the most crucial moment in his career, to be asked to do the one thing he was extremely good at, when everybody knew he was going to try to do it—and he still did it.

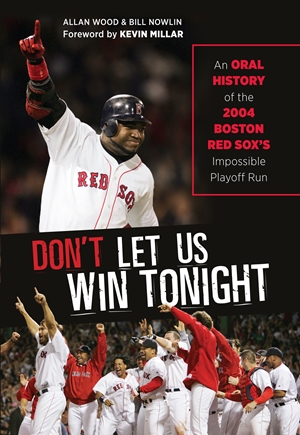

This excerpt from Don’t Let Us Win Tonight: An Oral History of the 2004 Boston Red Sox’s Impossible Playoff Run is printed with the permission of Triumph Books. To order the book, please click here.